Throughout the history of antitrust legislation in the United States, its stated purpose has been to protect consumers from corporations gaining monopoly powers over the prices and quality of goods and services. Lina Khan’s radical view of antitrust has changed that.

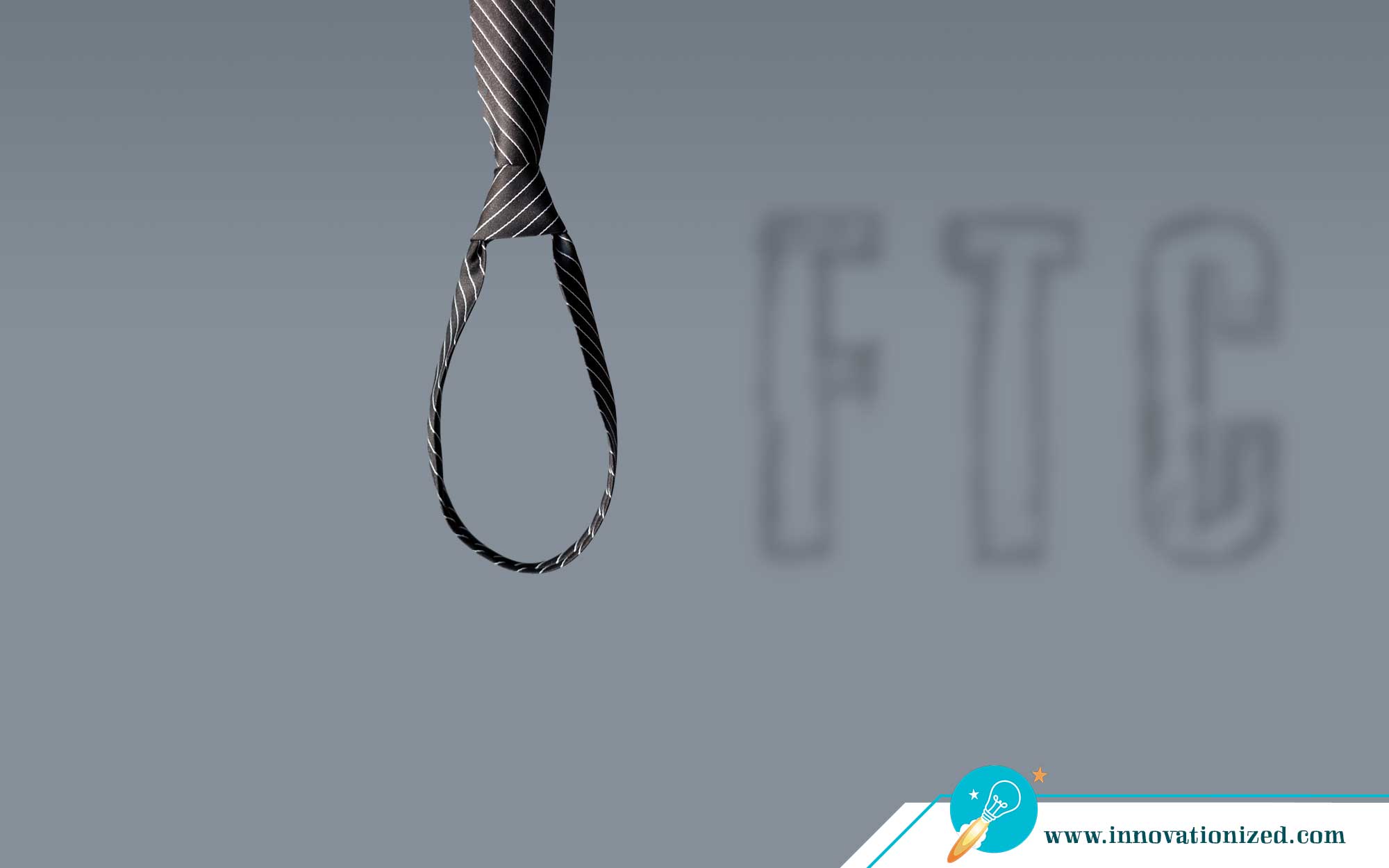

Lina Khan was appointed the new Chairwoman of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) by President Joe Biden in 2021, has a radical new strategy for leveraging antitrust law against the American technology industry: She plans to go after budding technologies generally, not just the ones under monopolistic control, in order to smother out the ambition of prospective technologists in its crib. And Chairwoman Khan has already begun her march against rising innovators which, if it continues, may dramatically slow humanity’s ability to make technological and scientific progress.

Rejecting Consumer Welfare

“Courts have applied the antitrust laws to changing markets, from a time of horse and buggies to the present digital age,” explains the Federal Trade Commission in a publication at ftc.gov. “Yet for over 100 years, the antitrust laws have had the same basic objective: to protect the process of competition for the benefit of consumers, making sure there are strong incentives for businesses to operate efficiently, keep prices down, and keep quality up.”

Chairwoman Khan is having none of this. Her sights are set elsewhere than on the old-fashioned “benefit of consumers.”

Back in 2018, when Khan was a Yale Law student devoted to antagonizing Amazon, the New York Times explained her novel view of antitrust enforcement in an article titled “Amazon’s Antitrust Antagonist Has a Breakthrough Idea” and subtitled “With a single scholarly article, Lina Khan, 29, has reframed decades of monopoly law.”

How Lina Khan has unleashed an unprecedented assault on start-ups with her vision of antitrust... Share on XKhan’s 2017 Yale Law Journal article “Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox” argued that Amazon was simply too successful to go on unmolested by government obstruction, the well-being of the consumers be damned.

“Her argument went against a consensus in antitrust circles that dates back to the 1970s — the moment when regulation was redefined to focus on consumer welfare, which is to say price,” the Times reports. “Since Amazon is renowned for its cut-rate deals, it would seem safe from federal intervention. Ms. Khan disagreed.

Over 93 heavily footnoted pages, she presented the case that the company should not get a pass on anti-competitive behavior just because it makes customers happy.”

Khan admitted to the Times that, “As consumers, as users, we love these tech companies.” But as her Yale Law Journal article says, “Animating these critiques is not a concern about harms to consumer welfare, but the broader set of ills and hazards that a lack of competition breeds.”

The article concludes, “To revise antitrust law and competition policy for platform markets, we should be guided by two questions. First, does our legal framework capture the realities of how dominant firms acquire and exercise power in the internet economy? And second, what forms and degrees of power should the law identify as a threat to competition? Without considering these questions, we risk permitting the growth of powers that we oppose but fail to recognize.”

As the Times summarizes, “The issue Ms. Khan’s article really brought to the fore is this: Do we trust Amazon, or any large company, to create our future?”

Expanding the Scope of Antitrust

Now that Lina Khan has been appointed FTC Chair, she has taken her views of antitrust applicability to a new level. Seemingly emboldened by her disregard for consumer welfare, she has dispensed with an assumption that was previously foundational in antitrust thinking: Its exclusive application to monopolies that have already formed.

Instead, Khan is aiming to prevent the monopolies of the future by preventing new technologies from being developed in the first place.

When the Times interviewed Khan in June, they asked her, “Can your work really rein in tech, which often outpaces rule-making and policy?” And in her reply, she explained that, “I think this goes back to being attentive to these next-generation technologies and next-generation innovations in nascent industries across sectors. Those can really help us tackle problems at the inception.”

The following month, Khan put her plan into action by filing an injunction to block Meta (formerly Facebook) from acquiring Within, a small virtual-reality start-up key to Meta’s plans to develop the “metaverse.”

In the lawsuit, which named Meta Chief Executive Mark Zuckerberg as a defendant, the FTC emphasized that, “…Meta could have chosen to try to compete with Within on the merits; instead, Meta decided it preferred to simply buy [the property].”

The significance of the move was not lost on The New York Times, which noted Khan was “upending antitrust standards” by shifting its role from dismantling monopolies to launching preemptive actions.

“Lina Khan may set off a shift in how Washington regulates competition by filing cases in tech areas before they mature,” the Times reported.

As the Wall Street Journal delineated in August, there are many reasons that Meta’s acquisition of Within would not remotely constitute the use or accretion of monopoly power. But as the Times explains, “At the heart of the FTC’s lawsuit is the idea that regulators can apply antitrust law without waiting for a market to mature to the point where it is clear which companies hold the most power.”

Smothering Technological Progress in Its Crib

With the advent of Khan’s radical new approach, the FTC is now working to achieve the exact opposite of what ftc.gov claims is the purpose of ensuring market competition through antitrust enforcement: “…lower prices, higher quality products and services, more choices, and greater innovation.”

This approach is not only likely to increase prices for existing technologies, but the initiative against the trade of technology companies will disincentivize the creation of new tech startups and thus reduce the amount of innovation and the choices of products on the market as well.

As the above mentioned Wall Street Journal article notes, it’s no secret that venture capitalists “often fund startups on the hope that they will be bought by larger companies.” And just like venture capitalists, profit-seeking investors and entrepreneurs of all sorts would be more likely to build tech startups in an environment of frequent acquisition offers than they will if that potential revenue stream is outlawed by the state.

The big companies will also be disincentivized from investing in developing new technologies, because they’ll know that antitrust crackdown will render such ambitions less profitable and more risky. And even when tech companies choose to pursue new technological projects despite this bad incentive structure, progress will be much slower because they’ll be forcefully prevented from capitalizing on the best new innovations of smaller companies, even though the smaller companies would benefit from their involvement or else turn down their offers.

Corporate Power Is Consumer Power

Technological progress is one of the key ways that human beings improve the quality of life for themselves and each other. Technology has significantly increased the average human life expectancy by diminishing the prevalence of disease, starvation, and even violence in human society. It has drastically reduced the portion of humanity engaging in dangerous and unpleasant labor for a living. And it represents the best chance of defending against climate change and other risks of the future without impoverishing developing nations to the point of mass starvation.

And the multi-polar next generation of the internet known as the “Metaverse,” which is the main area of technology currently in the sights of Chairwoman Khan, is no exception. The Metaverse could dramatically increase economic prosperity by opening up the labor market in profound new ways, allowing whole new areas of knowledge and experience to become widely available, and improving sustainability by allowing a vast range of resources to become interchangeable for one another.

So beyond Chairwoman Khan’s explicit abandonment of consumer welfare lies an implicit crusade against it. The premise that private businesses should be prevented from becoming economically powerful misses the point that how they do so is by successfully building and distributing products that large numbers of consumers want to use. By preventing business deals and investments that would have happened if left up to the free market, the FTC is preventing consumers from accessing products that would have either benefited them on their own terms or failed in the market.

How Lina Khan has unleashed an unprecedented assault on start-ups with her vision of antitrust... Share on XIn his book Human Action, the economist Ludwig Von Mises explains the consumer’s role in which new technologies become successful on the free market:

“What counts alone is the degree of superiority secured by the new invention as against old methods. Superiority means reduction in the cost of production per unit or such an improvement in the quality of the product that buyers are ready to pay adequately higher prices. The absence of a sufficient degree of superiority to make the cost of transformation profitable is proof of the fact that consumers are more intent upon acquiring other goods than upon enjoying the benefits of the new invention. It is the consumers with whom the ultimate decision rests.”

Corporations wielding political power through government corruption is another story, but the voluntary market exchanges that Chairwoman Khan is seeking to prevent are economic rather than political, and thus by opposing corporate power in this form, the FTC is opposing consumer power just as much.

The only kind of power it is looking to advance is its own, to the detriment of corporations and consumers alike.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.