If only there was a material, one that could be used for thousands of different uses, with a diverse range of properties, from rock-like, hard and heavy, to delicate, lace-like, light, and transparent, what a miracle that would be! If that material came from the “waste” byproduct of another material, even better.

There is such a material. Plastic.

Synthetic plastics are a very recent invention, yet they have come to be a dominant material in our lives. Our houses, our cars, our clothes, encase us in plastic. Much of what we touch and consume, comes wrapped in it.

It is also, we are told, overflowing in our landfills, polluting our rivers and oceans, poisoning people and killing wildlife. From the innocuous drinking straw to plastic cutlery, grocery bags and food containers, plastic is seen as a threat to humans and wildlife. Increasingly, plastic items are subject to outright bans or taxes around the world.

What is the truth about plastic? It’s not what you might think.

What is Plastic?

The word “plastic,” comes from the Greek word “Plastikos” meaning any pliable material that can be shaped or molded by heat or pressure (or a combination of heat and pressure).

Plastics are synthetic, organic polymers. They are organic because they include carbon, the element essential to life. Due to their repeating (polymer) molecular structure, plastics are very versatile, moldable, pliable, and durable.

Shellac was used to make the first gramophone records from 1898 until the late 1950s. – Yale University Library

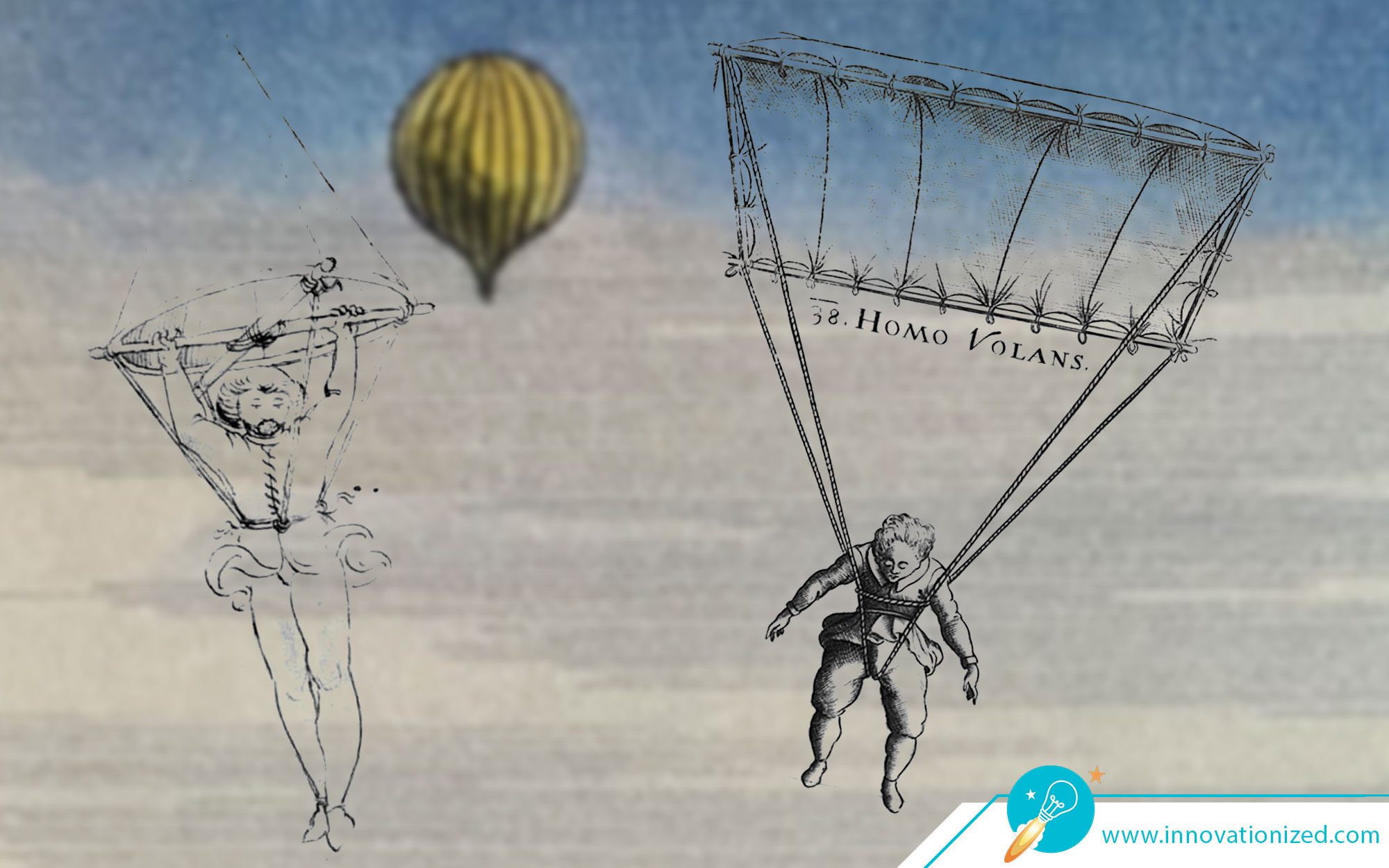

Humans have used some form of plastic for millennia, including amber, horn, hoof, and turtle shells. They were used for their beauty in jewelry, and for their ability to be heated and molded or carved into new shapes. Later, other natural plastics, joined the staples of ivory and turtle shell, such as shellac (from secretions from lac beetles from India), and gutta-percha (latex rubber from trees in Malaysia).

However, a growing population combined with desirable new technologies, such as the automobile, electricity, and the gramophone, meant a rising demand for these natural polymers.

How Plastics Saved the Elephants, Turtles and Others

Around the mid-19th century, with a growing and increasingly affluent population in Europe and the United States, worldwide demand for nature’s useful materials was growing. Ivory was an important material, being used in goods such as jewelry, musical instruments, and utensils.

Europe and the US were consuming two million pounds of ivory a year, equivalent to 160,000 elephants, and posing a major threat to the dwindling elephant population. [1] Turtles too, were in demand for their shells, with about 60,000 hawksbill turtles a year being killed for their shells. [2]

In 1863, a billiard ball manufacturer, Phelan & Callander in New York City, offered a reward of $10,000 to anyone who could provide a substitute for ivory.[3]

Celluloid Saves the Elephants

John Wesley Hyatt of New York, set to work on the problem, and in 1868, invented the first commercial semi-synthetic plastic, celluloid.[4] It was manufactured from cellulose from wood and cotton. Celluloid was heavy and hard like ivory, making it an ideal substitute of ivory. It was also cheap to make, and easily molded, carved, and colored, and required little or no finishing. Although there were challenges with the early forms of celluloid, it soon began to replace ivory, horn and tortoise shell as the material of choice.

The development of celluloid provided an abundance of better and cheaper products, and elephants and turtles were no longer hunted to near-extinction.

“Shellac was used to make the first gramophone records from 1898 until the late 1950s.”

– Yale University Library

The invention of other plastics quickly followed.

The first fully synthetic plastic was Bakelite in 1907, invented by Leo Baekeland. It had important differences to celluloid that made it extremely useful in different ways. It was hard, durable, and could be molded with precision, and mass produced cheaply.

Bakelite was used in everything from pipes, cigarette holders, jewelry, pens, to electrical hardware. Bakelite was an insulator, and was used in electrical switches and boxes, which made them safer. It also replaced metal for lids and screw on tops. Metal lids and caps were difficult to open, fit poorly, and led to contamination and deterioration of the contents in the container.

The New Plastics were critical to the success of the Allies in World War II.

In 1932, DuPont invented synthetic rubber. Just a few years later, during World War II, the Japanese gained control of the rubber plantations in Asia, and cut off the Allies rubber supply. Given the critical importance of rubber to the war effort, this could have been catastrophic, if it were not for the invention of synthetic rubber.

“The construction of a military airplane used one-half ton of rubber; a tank needed about one ton and a battleship, 75 tons. Each person in the military required 32 pounds of rubber for footwear, clothing, and equipment. Tires were needed for all kinds of vehicles and aircraft.”

US Synthetic Rubber Program, American Chemical Society

In 1935, the commercial production of polyethlene began, just prior to the war. It too proved pivotal. According to Sir Robert Watson Watt, the inventor of radar, without polythene the development of radar would have been impossible.[5] Radar was crucial to the war effort. It gave the Allies the ability to “see” long distances, day and night, and was used on land, in aircraft, on ships, and even on artillery shells (for proximity fuzes).

Other plastics played important roles in the war. Vinylite® (used as liner in the US M1 helmet) is credited with reducing battlefield casualties by 8%, thus saving 76,000 soldiers from death or serious injury. [6]

Perspex, commercially produced in 1934, provided lightweight, shatterproof windows and gauges for aircraft, improving their performance, and making gauges and windows less likely to break.

Plastic Today

Plastic plays vital roles in every aspect of our lives, from the clothes on our bodies, the shoes on our feet, to the glasses and contact lenses we wear; to the vinyl siding on the outside of our homes, the plumbing and electrical systems, and the appliances and all the devices and gadgets inside.

Plastics are vital to the healthcare industry and to the functioning of hospitals, from the drugs, protective wear, medical devices, packaging, tubing, and the very hospital infrastructure itself, including the floors, ceilings, lights, curtains, bedding, cabinets, tubing, bags, cabling, plumbing and more.

Plastics also inhibit the spread of disease between patients and staff, and ensure the integrity of our drugs. They go into virtually all medical devices, and improve performance and make equipment lighter, more portable and durable, and cheaper.

“If it weren’t for plastic and Dr. West’s Miracle Tuft toothbrush, we’d still be brushing our teeth with boar bristles.”

-Nigel Duckworth, Innovationized.com

Plastics are not only important in the treatment of disease, but they protect us from getting sick in the first place, keeping food, cutlery, and many other items sterile.

They are essential to ensuring the freshness and safety of our food throughout the supply chain. Lightweight, yet tough plastics, enable food and beverages to be transported around the globe, maintaining freshness and flavor, while minimizing damage and preventing contamination. They enable consumers to see and handle foods safely, while providing an impervious barrier to bacteria and contaminants.

We are particularly vulnerable when it comes to instruments and food that goes into our bodies. The much maligned “single use” plastics are particularly valuable, ensuring that items like syringes, straws, and utensils, remain protected and sterile as much as possible.

“Both deaths and ER visits spiked as soon as the [plastic grocery bag] ban went into effect. …deaths in San Francisco increase by almost 50 percent, and ER visits increase by a comparable amount. Subsequent bans by other cities in California appear to be associated with similar effects.”

– Jonathan Klick and Joshua D. Wright, “Grocery Bag Bans and Foodborne Illnesses” [7]

It’s thanks to these plastics, and many others, that human life is so much better, and nearly every product that uses plastic, is better, cheaper, and more durable than its predecessors (if it could be manufactured at all without plastic).

The Miraculous Material

Miraculous adjective – highly improbable and extraordinary and bringing very welcome consequences; transcending the laws of nature.

If there is a class of miraculous materials, one that can be used for thousands of different uses, with a diverse range of properties, from rock-like, hard and heavy, to delicate, lace-like, light, and transparent, and everything in between, that would be quite a material. If that material came from the “waste” byproduct of another material, even better.

Plastic comes in all those forms, and more. From billiard balls (celluloid) and bulletproof vests (Kevlar), to transparent and flexible (cellophane) or rigid (Perspex), or delicate and silk-like (nylon), plastic does it all.

Plastic has transformed our daily lives, improving nearly every area of life and industry, including apparel and footwear, art and entertainment, construction, medicine, sports, transportation, and more.

For example, plastic ensures our food and beverages are fresh and safe from contamination, preserving their taste, extending their shelf-life, making them more affordable, while reducing packaging waste.

Plastic provides similar advantages for drugs and medical equipment, ensuring they are free from contaminants, preserving their shelf-life and effectiveness, while making them more economical.

In prosthetics, light, strong, flexible plastic replaced heavy, uncomfortable, and expensive leather and wood. Modern prosthetics are light, comfortable, form-fitting, better performing, cheaper and more long-lasting.

Plastic made possible countless new medical devices, including SynCardia’s revolutionary artificial heart. The heart is made of segmented polyurethane solution, which resists fatigue, gives it a high degree of strength and biocompatibility, minimizing the risk of an adverse response from the recipient.

Plastic also enabled the computer revolution, the internet, smartphones, and space travel.

Through their versatility, their ability to seal, and their ease of manufacturing, durability, lightness, biocompatibility, and cost-effectiveness, plastics make possible a host of new products and technologies. They also improve existing products, making them cheaper, safer, longer-lasting, and more effective and efficient.

This is why plastics are so ubiquitous. They solve a myriad of problems really well, and more cost-effectively than the alternatives.

“Reduction in vehicle weight can result in a 6% – 8% increase in that vehicle’s fuel economy, according to the Department of Energy.”

American Chemistry Council

Prior to the invention of synthetic plastics, we relied on the natural world for our materials, which primarily meant using metal, wood, stone, and animals (skins, bone, shell). The invention of synthetic plastics transformed manufacturing, and gave rise to countless new, better, and cheaper products, and reduced our reliance on living resources like trees, animals and insects.